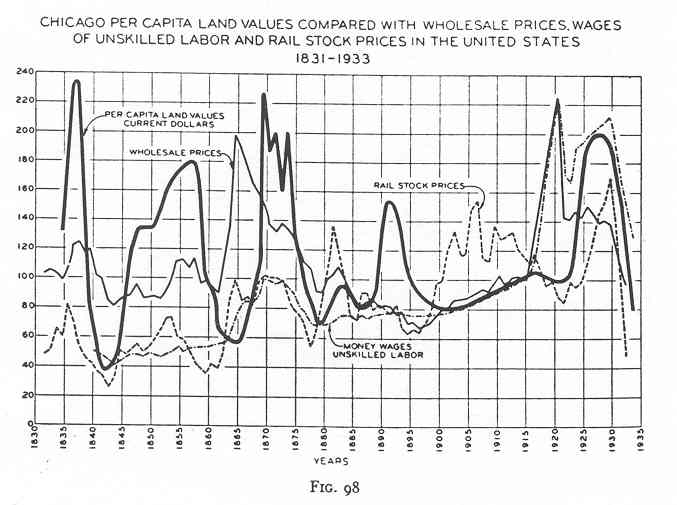

The downturn at wars end should not be lightly dismissed. It ushered in some profound changes that set the base for the whole 1920's experience in America. Returning US soldiers, some five million of them, plus further immigration into the country, caused a housing shortage, particularly since for the past five years or so all production efforts had been for war supplies. Hoyt notes that housing rents doubled from 1919 to 1924. This brings in some good rent theory here; returns to owners of existing buildings increased, the capitalized rate of return went up, which attracted others who started building to take advantage of the higher rents on offer, pushing up urban land values as demand for building lots increased. Hoyt notes that by 1926, US urban land values had doubled from levels at the end of the war. Chicago land values were up 150 percent by 1926, from 1918 values.

On the other hand, agricultural America went into decline after the boom of wartime demand. Australian and Argentinean wheat was again available for European consumption and the few souls who survived the trenches and gas of Verdun could go back to farming in Europe themselves. It was discovered also, that a large surplus of commodities had been stockpiled by the US during the war, causing a sharp decline in prices once this was realized. Farmland values dropped of course. Hoyt says they halved. As the 1920's wore on, more and more country banks were suspending operations and closing. This fact never seemed to make it to Wall Street however, or was ignored in the rush to get rich. This then is the background to the 1920's.

The Great War did one more thing relevant to our story of boom and bust. It awakened a US public to the virtues of investing through the buying and selling of liberty bonds put out during the war era. A whole new class of investors was thus created: "people who had never before owned a bond or a share of stock in anything." (Holbrook, The Age of the Moguls, page 235.) And come the 1920's there arose plenty of men willing to sell the public whatever they wanted.

DOW 1919-23 Chart

The Roaring Twenties.

1921 to 1929, and the eventual great depression which followed, is an era of US history that has been intensively studied and scrutinized. It is a history (or at least a result) well known to most, so one need not repeat the whole story again here. There are a few misconceptions, however, that require clearing up and a few points that ought to be further highlighted.

The 1920 downturn promptly reversed itself the following year. That all-important lending rate had much to do with it. "In the fall of 1921 the national economic picture reversed itself in sixty days," said John Brooks. (Once in Golconda, page 41.) "The postwar depression promptly ended, and a new and more durable boom replaced it…The recovery was officially smiled upon and encouraged by the Federal Reserve System, which, beginning in 1921, progressively reduced its discount rate from the postwar peak of 7 percent all the way to 3 percent by 1924." The discount rate set by the Fed was flashing easy credit conditions once again.

Pretty much simultaneously, the new Treasury secretary, Andrew Mellon (possibly at this time America's wealthiest citizen and banker and who resigned as director of more than fifty corporations to accept his new government position) embarked upon one of the most systematic and vigorous tax reduction programs yet seen. As president Coolidge famously expressed it, 'the business of America is business'. The wealthy Philadelphia banker Andrew Mellon, agreed. "...government existed mainly to facilitate business, indeed it was no more than a business itself. Mellon set about improving the conditions for business by reducing the top rate of income tax from 65 to 32 percent, cutting corporate taxes to 2 and a half percent, and slashing capital gains taxes. As a result of these tax cuts the rich had more money to invest in stocks, companies reported higher after tax earnings, and more of the profits of speculation could be retained by the players." (Chancellor, Devil Take the Hindmost, page 197.)

What no historian ever picks up about such tax cuts of course is the effect on land value. The dramatic savings in income taxes were quickly capitalized into higher land values. (For an excellent proof as to why this is so, Chapter 3, Rent and the Dysfunctional Economy, in George Miller's On Fairness and Efficiency: The Privatization of the Public Income over the past Millennium, is suggested reading.) "The Revenue Act (1924) gave taxpayers a 25 percent reduction retroactive to 1923 income, increased personal and surtax exemptions, and brought the top rate (which had stood at 73 percent in 1921) down to 46 percent in 1924. This coincided perfectly with the land boom in 1924/25." (Harrison, The Power in the Land, page 134, note 17.) And the land boom was fed further of course by the easy credit policies of the banks. "A particularly ominous development was the expansion of the banking system itself for the specific purpose of financing real estate promotion and development. Real estate dominated the policies of many banks, and thousands of new banks were organized and chartered for the specific purpose of providing credit facilities for proposed real estate promotions. The greater portion of these were state banks and trust companies, many of them were located in the outlying sections of the larger cities or in suburban regions not fully occupied by older and more established banking institutions." (Herbert D Simpson, Real Estate Speculation and the Depression, page 164, and quoted also by Hoyt, page 385 note 10.) It is the rise of the stock market and its subsequent collapse that everyone remembers having heard about the 1920's. But there was also a big, if not bigger boom in real estate. Hoyt, page 234, indicates the price of urban land doubled between 1920 and 1926. Such an increase would never go unnoticed and would have left land and house owners feeling much wealthier than before.

The 1920's land boom.

The Sooners had settled Oklahoma, ostensibly the last of the US frontier, within 24 hours on that memorable 1889 April day. However there was found to be just a little frontier left, in Florida, though part of it spent time underwater. We have noted already how by 1926 urban land values had doubled from the levels of 1919. Quite an increase in a very short space of time. How this came about in Florida is a story worth telling. It began this way:

In the 1850's, the state of Florida bought from the federal government millions of acres of land classified within the state as swamp under the Federal Swamp and Submerged Lands Act. For a while, development was hindered by legal and debt problems, but eventually in 1881 the way was cleared for future land reclamation and agriculture. This in turn created a reason for the entry of the railroads, for the carrying of freight and farm goods.

It could be said that the story of Florida land speculation started with the railroads, of which there were originally three though Henry Flagler's East Coast line into Miami in April 1896 really got the ball rolling with a connection directly to New York. A short time later, the already existing but small Miami business community went nationwide with advertisements recommending Miami as the place "where summer spends winter" (Miami Herald, September 15, 2002) though to get to the beaches one still needed a boat until 1913 when the Collins bridge allowed the motor car all the way into the city. Wealthy northerners began building winter residences as Henry Ford's 'tin lizzies' (Model T's) started rolling all the way down south.

Early Southern farmers had held the belief that Florida land was a bit too sandy for profitable farming, but the railroad, with the carriage of more and more crops proved the belief wrong. Soon, "people across the farm belts of the United States were heard sprouting the railroad promotion slogans, 'below the frost line' and 'ten acres and independence'." In 1910, one thousand dollars could get you a piece of Florida acreage and a cottage, hence the railroad promotions. And such an investment could yield $3,400 in tomatoes in one year. "Despite the need of huge doses of fertilizer and heavy labor, Southern farmers (now) considered Florida an agricultural paradise." (floridahistory.org). At the same time, the railroad owners built huge (massive) hotels at their railroad heads and other strategic sites along the way, kicking off the winter hotel resort industry. (If arriving by train, it was not uncommon to observe the train engineers stop the train to check their game traps along the rail bed.) The Spanish-American war of 1896, fought over Cuba, also focussed attention on Florida, particularly the city of Tampa. A construction boom followed, with plenty of the US soldiers returning to Florida for the cheap land to start farming.

By the early 1900's, the need for more land in Florida was becoming apparent (to developers at least). In 1906 began the serious work of dredging canals to remove some of the water from the everglade areas. (Though there were those that wanted such areas preserved rather than built on.) Even the feasibility of complete drainage was discussed in a report at federal government level. One report, the Wright Report of 1909, claimed that "approximately two million acres of Everglades land could be reclaimed by digging eight canals from Lake Okeechobee southeast through the Everglades, at a cost of about one dollar per acre." Land sales boomed. (everglades.fiu.edu/reclaim/timeline/timeline6.html) Real estate men lost no time in promoting the benefits of such land investment, auctioning off large swathes of un-drained swamp. Said one buyer in 1911: "I have bought land by the acre, I have bought land by the foot but by God I have never before bought land by the gallon." The Wright Report however, in 1912, was shown to be flawed (water from nearby lakes was flowing into unfinished canals) curtailing Florida's first (mini) land boom, with twenty thousand purchasers of land demanding their money back.

World War I also brought benefits to Florida since Europe was for the duration of the war no longer a vacation destination for wealthy Americans. In 1915, Florida State instituted a substantial road building program. Four years later, the Dixie highway was completed; one road linking Michigan State all the way south to Florida. Now, as highway construction increased in earnest, Florida was open to the middle class as well.

This road building program recognized early the likely economic impact of the new automobile and their drivers and holidaymakers, the 'tin can tourists' as they were called. "With the arrival of the twentieth century, Americans continued in the pioneering spirit of the forebears and looked upon the automobile as a new way to explore the unknown. Throwing a tent in the back of the car, thousands of Americans set out to enjoy the back roads of the United States. Carrying the extra gasoline in five-gallon cans, plenty of canned food, and extra tires strapped to the fenders, these intrepid souls began an exploration of the North American continent with a thoroughness that put Lewis and Clark to shame. These tourist became the symbol of another 'new generation' of Americans, restless, adventuresome and filled with boundless curiosity." (Nick Wynne, Tin Can Tourists in Florida.) These mostly northern tourists took their name from their b.y.o. tin-can cuisine carried in the car, and "with the postwar (WWI) drop-off in industrial production in the north, many laid off workers still had a cushion of money - and a Ford Model T. Instead of despairing, they decided 'Let's take a vacation'." (tincantourist.com/ tidbits.html) En mass they headed to Florida.

Sometimes several families all piled into the one auto. "What started with chilly Northerners seeking a slice of America's newly civilized frontier on which to vacation or to retire, soon turned into one of the greatest social and economic movements of population and capital in the history of the world." (Smithsonian magazine, January 2001, quoting a promoter of the time.) And the kings of this movement were the land developers. "If the railroad barons dominated the Gilded Era, the great land developers dominated the Florida of the land boom. These people didn't just design developments; (they) created entire cities. These architects and engineers did more than build houses; they created a way of life that became known throughout the world as the Florida lifestyle." (floridahistory.org/ floridians/1920's.html)

Developer Dave Davis dredged two mud islands in Tampa bay and built Davis islands, complete with yacht clubs, hotels, tennis courts and more. Barron Collier, who made his fortune from streetcar advertising, put together 1.3 million acres of the state after visiting Florida in 1911, then built the city of Naples and Marco Island into winter resorts that proved wildly popular. (It was Collier that actively pushed early efforts to drain the Everglades.) Carl Fisher built Miami Beach, putting his substantial fortune from the manufacture of automobile headlamps into the development. Locals literally gasped as Fisher proceeded to fill hundreds of acres of swamp with sand dredged from the bay, top it with thousands of tons of Everglade topsoil and then build hotels, golf courses, yacht clubs and polo grounds.

A born promoter, Fisher started his working life at age 12 selling newspapers on the railway. Sales soared after he started flashing a photo of a naked woman from underneath his jumper. This time, to draw attention to his Miami Beach development, Fisher "brought in a circus elephant, imported a polo team from England, dressed young women in risqué bathing suits, and started taking pictures." (pbs.org Mr Miami Beach.) The press loved it. Soon, every paper in the country was carrying pictures of suitably clad (or rather un-clad) women on the beach in Florida. All of a sudden, Florida was the place to be.

Fisher's promotions sparked a national hysteria for Florida real estate. Said one historian: "Fisher was the first man to discover that there was sand under the water…(sand) that could hold up a real estate sign. He made the dredge the national symbol of Florida." (theledger.com/static/top50/pages/ fisher.html) By 1925, Florida was known for wide avenues, golf courses, palm trees and sun drenched beaches. Southern Florida became the American Riviera: "a place to vacation, a place to be seen, a place to make money." Could Florida real estate be anything else but a sure thing ?

Sea-front lots were offered to investors, especially wealthy northern investors, with just 10 percent down. And of course it was implied that by the time your second installment was due, your real estate would have doubled in price, or thereabouts. Lots 40 miles from Miami were going for $20,000, a beachfront lot for $75,000. (digitalhistory.uh.edu). But most of the real estate activity took place in the 100 mile stretch from Palm Beach to Miami. By early 1925, those who had bought in '23 had seen gains of 600% or more. (buyandhold.com Florida land boom) Lots were being sold and re-sold many times over. Real estate men lined the railroad stations waiting for their buyers, or had students (binder boys) stand at the lot sites (thus avoiding the blazing mid-day sun) taking bids. 1925 saw $1 billion flow into Florida construction. Wall-Streeters bought up, small town America converted its savings into Florida lots, even wealthy Europeans came to Florida to see the action for themselves.

So many citizens were now pushing Florida real estate that the municpal authorities were having trouble finding staff to carry on essential services; most of the policeman, firemen and other employees had quit to do the same thing, buy and sell land. The Miami authorities resorted to grabbing the sharecroppers from the hills of Georgia and putting them in uniform, despite the fact many, if not all, had never before worn shoes let alone some sort of authoritarian outfit. The desired improvement in law and order was not achieved. Towns north of Florida reported a severe slump in the movie business because so many theatre-goers were leaving town to travel South. Warehouse managers even as far away as New York were reporting no space left because of all the furniture they were having to store on account of those who had sold up and travelled south to trade real estate. Said the Indianapolis Times: "Literally thousands of people are leaving our state in search of something for nothing in the land of oranges and speculators." (Thomas, page 198.) The Massachusetts Savings Bank Association complained that more than one hundred thousand depositors had taken their money out of the state's banks and headed to Florida to buy land.

Readers of history might have seen such a story before. Something dependent solely on ever rising prices will not last indefinitely. Some minor difficulties arose late in 1925. In this year, the newly designed federal income tax laws (from 1913) pushed income tax officials to start studying real estate records for understated, or indeed not stated assessable profits. Anti Florida propaganda mounted up north. That October, a nation wide rail strike halted deliveries of building material into the state. Then, in early 1926, the Prins Valdemer, filled with lumber, overturned in Miami harbor, delaying shipments of further building supplies for additional weeks and blocking the harbor for some time. Further bad news followed in late March when the US stock market took a dive throughout the whole month. (The Dow fell from 162 to 135, bottoming on the 29th and 30th March, though going on to recover strongly by June.)

Perhaps this gave some a little time to think, for money and credit seemed to be thinning out a little too. The flow of speculators along the Dixie Highway began to reverse a little, as a few prospective buyers headed back north. Those who did so avoided the hurricane that hit Miami on September 18, 1926, killing almost 400 and injuring thousands. There had been nothing like this hurricane since 1910, but back then of course there was little of man made consequence to destroy. As the 125 m.p.h. winds swept in from the Atlantic and moved counter clockwise over Lake Okeechobee, the south end of the lake dried up. Then, as the storm passed, it brought a wall of water to the towns of Belle Glade and Moore Haven, drowning 300. The news of people drowning in a wave, thirty miles from the Atlantic Ocean, stunned people right round the world.

(floridahistory.org/floridians/1920's.htm)

Reconstruction began immediately of course, but nature struck again with another hurricane in 1928, this time closing the Florida land mania for decades to come. The boom was bust. Said historian and a former St. Petersburg Florida realtor, Walter Fuller: "The 1925 Florida land boom just ran out of fuel in the late fall of 1925 and quit - we just ran out of suckers, that's all." The Marx Brothers parodied the whole Florida episode in their 1929 production of The Cocoanuts; opening a hotel, auctioning off plenty of land, naturally, thwarting a jewel heist and generally carrying on as only the Marx brothers could do. All the major real estate players went bust and lost every cent.

Meanwhile, in Chicago, the cycle played out pretty much the same way as the build up to previous Chicago booms, only this time the public was marketed to by telephone, with land promoters regularly calling absolutely everyone listed in the newly available telephone directories to gain an appointment with real estate sales representatives. "Free train rides and free lunches lured the prospect to the property where promises of a safe investment coupled with a great speculative profit led many people of small means to invest their life savings." (Hoyt page 257.) Like lambs to the slaughter; Baaaaa…

The increasing speed of transportation and communication was massively changing the urban landscape too, not just in Chicago, but in all cities. A surge of population outwards from city centres had begun (continued in earnest after 1945) where new homes could be built with some impressive modern amenities like plumbing and bathroom fittings and fixtures. This was all related to the speed of the new automobile and it added up to a lot of demand for the new way of suburban living, with much of it, because of land price, to be built on credit. And as Rothbard so ably noted: "Credit expansion always concentrates its booms in titles to capital, in particular stocks and real estate, and in the late 1920's, bank credit propelled a massive real estate boom in New York City, in Florida, and throughout the country. These included excessive mortgage loans and construction from farms to Manhattan office buildings." (Rothbard, A History of Money and Banking in the United States, page 418.) As a self-confessed libertarian however, Rothbard proved unable to see the connection of the capitalization of government granted licenses and privileges into tradable commodities as the true cause of the real estate cycle, though libertarians in general are good when it comes to an analysis credit and the role played by banks.

The new era.

No doubt the mid 1920's income tax cuts, courtesy of treasury Secretary Mellon, influenced the stock market too. And the continuing credit expansion brought forth plenty of imaginative ways in which to spend such cuts. To gain leverage was the key. Call loans were already a common feature of the market by this stage, as we have seen. So buying stocks on margin was not new to this era. But the activity was practiced far more widely. And no longer just for stocks. The concept was applied to many other consumer items as well. Now, a Model T Ford could be had with say $100 down and the balance of the price, perhaps another $300, financed through the dealer with a contract to pay it off steadily each month.

The car itself became the collateral for the loan. Listed corporations saw the benefits too that could be had with leverage - borrowing - to increase earnings and hence stock prices. Investment trusts used this process extensively. A new trust company might float on the exchange, raise some money, then invest the proceeds immediately back into the market with the purchase of listed stocks, also on margin. Certainly by 1927, it was conceivable that a margined individual buyer of a share in a listed investment trust, was buying a trust that owned stocks that were margined, and that possibly even owned shares in other investment trusts. Leveraged trusts buying other leveraged trusts. A small movement of the price could indeed increase one's wealth substantially, provided of course that prices went up…

And prices did go up, all decade. Yet another new era was truly believed to be underway. President Coolidge in his 1925 inaugural address said: "We appear to be entering an era of prosperity which is gradually reaching into every part of the nation." The public had no reason to doubt him. The Fed had solved the business cycle once and for all: management was learning to operate at lower levels of inventory; leaders of industry were now better educated than ever; mergers were promising greater economies of scale; and investment trusts could be seen ameliorating the speculative fluctuations (according to Irving Fischer at least). One professor, Paul Nystrom of Columbia even concluded that the nation, now 'dry', could increase the efficiency of its workers by switching demand from alcohol to "home furnishings, automobiles, musical instruments, radio, travel, amusements, insurance, education, books and magazines." Said John Moody, founder of the Rating's Agency that bears his name: "No one can examine the panorama of business and finance in America during the past half dozen years without realizing we are living in a new era."

Banks were of course very much involved in what was happening, and the 1920's saw a number of developments in their systems of handling payments and in their record keeping; huge increases in efficiency. "Telephones and typewriters, calculating machines and addressing machines had of course made their banking debut well before the First World War but this equipment was rarely found outside headquarters. Record keeping in small banks had been dominated by hand written ledgers and registers of securities; the only mechanical aides were coin weighing scales and the cumbersome hand presses used for wet-copying manuscript documents. In the interwar period by contrast, banks introduced ledger posting machines, dictaphones, loose-leaf binders and card indexes not only at their head offices but branches as well." (Edwin Green, Banking: An Illustrated History, page 108.) And it was women who were mainly recruited, in quite large numbers in fact, to take charge of operating the new machinery, giving many a new found independence and spending money.

As for the new era, this was not the first time one had been seen on the horizon. As far back as 1825, Disreali had asserted that the boom of 1825 (in England) would not turn to bust because the era was so different to times past because of the superior commercial knowledge then available. (Devil Take the Hindmost, page 191.) In 1928, the outgoing president, President Coolidge took the unprecedented step of publicly stating that he didn't believe brokerage loans were out of hand. According to his official statement: "The rise in outstandings simply paralleled increases in bank deposits and the amount of securities on the market." Privately though, he told a journalist: "If I were to give my personal opinion about it, I should say that any loan made for gambling in stocks was an excessive loan." (Fridson, page 69.) The incoming president, Herbert Hoover, even declared at his 1928 presidential nomination acceptance speech that the end of poverty was in sight.

Politicians and their speeches, why do we ever vote them in ? Politicians making any public announcement, no matter what, will always have some sort of agenda attached to what they say. This may or may not be obvious at the time of the statement, and is rarely what you, the investor, need to hear.

DOW 1920's Boom Chart

Perhaps though, this time, things really were a little bit different. For the first time ever, at least in the US anyway, woman was exercising her innate speculative talents. And for the newly independent, freedom loving gal, there was no better symbol of it than to while away the day watching the ticker in special rooms set aside for them in the hotels along Upper Broadway. "...gum-chewing blondes (and) shrinking spinsters who looked as if they belonged in a missionary-society meeting," (Chancellor, page 204, quoting the North American Review of 1929) could be found watching the market all day: a development no longer to be sneezed at either. Some figures were suggesting women now owned 40 percent or more of the nation's wealth and 35 percent of market turnover was believed attributable to them. They held about one-third of the stock of US Steel and General Motors, and perhaps half of the stock of Pennsylvania Railroad, dubbed the 'petticoat line' as a result."

At the end of the days trading, the girls could take their hard-earned rest and relaxation out on the road, in a newly bought - and paid for out of profit - Ford, Buick or Studebaker. Though not everyone approved. Preachers were heard lamenting the auto as nothing more than a 'house of prostitution on wheels'. The Lady Bulls: they spent the household money, why shouldn't they know better than hubby, which shares to buy it was reasoned. And they were said to be quite sporting losers too. One lady speculator, upon losing a million, said: "I had a perfectly stunning time while it lasted." (Chancellor, page 205, quoting journalist Edwin Lefevre.)

The (speculative) orgy hit a minor bump in the road in October of 1929. Writing in Forbes magazine as early as 1928, Richard Schabacker perceived a possible tightening of credit as the main threat to a continuation of the bull market. "There can be little doubt", he declared, regarding the steep rise in stock prices since 1921, "that the underlying cause for such advances has been easy money." (Fridson, page 68.) A healthy business climate and benign government policies had contributed, according to Schabacker, but only as background factors.

The Peak

"At first it seemed as though the market rise was a once-in-lifetime chance to make money with little or no risk. But as stock market prices continued to rise, many began to believe that the rise would be permanent, that the growth curve would be unending. In prospect, this conclusion was reasonable, for the nation was engaged in a great expansion, profits were rising, and conditions seemed sound."

So said Robert Sobel, in The Great Bull Market: Wall Street in the 1920's. Conditions always do seem at their best right at the top. This is of course the time when everyone is at his or her most bullish moment. And the Twenties were not called roaring for nothing. Another writer, Frederick Lewis Allen, who lived through the Twenties and wrote his account of it in Only Yesterday, described the times thus: "The rich man's chauffeur drove with his ears laid back to catch the news of an impending move in Bethlehem Steel; he held fifty shares himself on a twenty point margin. The window cleaner at the broker's office paused to watch the ticker for he was thinking of converting his laboriously accumulated savings into a few shares of Simmons." Allen continued with the story of a brokers valet who made nearly a quarter of a million dollars in the market, of a trained nurse who cleaned up thirty thousand following the tips given her by grateful patients. Said a new book released August 1929 titled, New Levels in the Stockmarket, "We have seen our country as it has grown at a tremendous rate in population; in wealth; and in the desire for finer things. Each generation has been thrilled by the rapidity of the progress which it has experienced in its lifetime. An optimistic psychology is in the air."

The decade had indeed been one for optimism and for crowds: "An era celebrated for excesses and exhibitionism in every facet of human behavior," said J. P. Chaplin. (Rumor, Fear and the Madness of Crowds.) Men hung suspended from planes whilst in the air, walked upon a tightrope between the highest buildings they could find, or tried getting out of strait-jackets suspended way above city streets. Women sought to emulate the swim of Trudy Ederle across the English Channel. Mid decade, August 24th, 1926 had seen one of the worst crowd riots in New York's history when around seventy thousand people took to Broadway, near 66th Street. Hundreds were injured or trampled underfoot as the crowd, mostly women, sought the best positions to view their recently departed heart-throb Rudolph Valentino, the movie hero of the Twenties, who lay in state in a nearby funeral parlor. "The idol of the hour…his movie love-making gave his female fans high voltage emotional jolts…men too came under his spell, and many copied his oiled back hair-do, gaucho style side-burns and broad bottomed trousers."

But as it was with Rudolph, so it is with the economy; there comes a time in every boom's life when the spigots must eventually be turned off. "Faced with the growth of speculation, the Fed changed tack and from February 1928 successively raised the discount rate until it reached 6 percent in August 1929." (Devil Take the Hindmost, page 198.) Rising interest rates can almost be guaranteed to bring on the circumstances of a contraction in credit, as banks and / or the monetary authorities attempt to do something about the speculation they have now judged to be excessive and to be stopped. (From a timing perspective W.D. Gann's chart 6, page 109, Wall Street Stock Selector, is instructive here: 2/28 to 9/29 is 19 months; 9/98 to 3/00 was 18 months. See the Indicators section, Gann timing, for more.)

There were a few Cassandra's along the way of course, warning that the expansionary conditions underway would not go on forever and that what went up had an ugly tendency to come down. Roger Babson was one. A market forecaster and economist of the time, he once again repeated his assertion in early September that a crash was imminent - though he had been saying that for several years. This time however, the market responded somewhat and the slight sell-off after September 3 was termed the Babson break.

It was in the middle of September (1929) when word was received from London that the business empire of Clarence Hatry had collapsed, amidst revelations of fraud. (It would eventually be found that Hatry had been creating and issuing false securities with which to finance his business dealings, eventually drowning in $65 million worth of debt to the banks.) "The bank of England reacted by raising interest rates, causing British investors to start selling their American investments and repatriating their capital." (Devil Take the Hindmost, page 214) Exactly why this collapse should have led directly to an interest rate rise is not all that clear. Nevertheless, the collapse may have been enough to have investors re-think their belief in future prosperity. The celebrated economic historian Charles Kindleberger said this of the Hatry revelations (page 71): "In September 1929 the Hatry empire collapsed in London. It consisted of a series of investment trusts and operating companies in photographic supplies, cameras, slot machines, and small loans, all of which Clarence Hatry was trying to parlay into a larger operation in steel. He was caught using fraudulent collateral in an attempt to borrow £8 million to buy United Steel, and his failure led to tightening of the British money market, withdrawal of call loans from the New York market, a topping out of the stock market, and the October crash." Again, that (un-looked for) event at the peak or just after that reveals the economic show for what it truly is; a show built on sand.

DOW 1929 Chart

On the 4th of October (30 degrees from Sept 3) Alfred Sloan, the head of General Motors, observed a sudden dip in car sales and announced that the end of the expansion was at hand. Markets seemed to have anticipated the news though, as the announcement marked a short-term low from which the Dow, as usual, retraced back by half, highlighting an overbalance of both time and price. After that, on my reading of things, market players began accentuating the bad news, ignoring the good - exactly the reverse of what had been going on before. This is the emotional aspect to markets, and can never be ignored. Gann believed this sort of market psychology unfolded according to time frames, which repeat, something I have come to accept, having seen it so often now it is undeniable. (180 degree time frames, days, weeks or months, can be especially important.) A more scientific assessment might call this process 'cognitive dissonance'; a process of selectively filtering information received, to put it in accord with one's own beliefs. Anything found to be in disagreement is ignored, indeed is actively avoided, until that is, the pain of avoidance becomes greater than the pain of recognizing the truth. This is why markets trend. Spot the trend early enough and one is well on the way to solid profits, just like Livermore points out.

In 1928, the Dow's new record high was made on November 28th, after which a marked sell off occurred down to the low on Dec 7th. The absolute top for the Dow came in on Sept 3rd, 1929, 270 degrees later. The subsequent crash was Oct 29th 1929, (56 days after the top) on volume of 16.4 million shares, a record that was not exceeded for 40 years. On that day, the ticker stopped, overwhelmed, and took hours afterwards to complete the day's records. Telephone lines overloaded with inquiries; the telegraph system could not process the number of margin calls made and the transatlantic cable broke. Sept 3 plus 52 days indicated Oct 24 the day to watch in advance, which came to be called Black Thursday on the day due to the unprecedented selling. On October 24 the Dow dropped 9 percent on volume of 12.8 million shares, only to eclipsed four days later on the 29th when the Dow dropped 17.3 percent.

On the night of the crash Groucho Marx, in an un-scripted moment in the Broadway version of the Marx Brothers comedy Animal Crackers, paused on stage to lament the plunge in stock prices; a line the New York crowd of October of 1929 would have instantly recognized. "Living with your folks, the beginning of the end," said Groucho, commenting on the possibility of marrying his usual foil, actress Margaret Dumont. "Drab dead yesterdays shutting out beautiful tomorrows. Hideous, stumbling footsteps creaking along the misty corridors of time. And in those corridors I see figures, strange figures, weird figures, Steel 186, Anaconda 74, American Can 138..." (Insana, Trendwatching, page 2.) Groucho had good reason to know the figures since it was believed he too had been speculating heavily.

That day, the 24th, the president of the stock exchange, Richard Whitney, had been attempting some theatrics of his own. Amidst what was desperate to be seen as not a panic meeting of wealthy bankers, once the hastily arranged meeting had broken up shortly after lunch, Whitney - J.P. Morgan's own broker - strode to the post where trading in US Steel took place and placed an order, showman like, for ten thousand shares of the company at 205, even though the most recent sale price and current offer was below 200. Thus was "the most celebrated single order in Stock Exchange history" (Brooks, page 125) transacted and a clear demonstration made of organized support for the market. The bankers committed some $240 million to buying, according to some later reports, but the market continued down anyway. Indeed, such was the further ferocious selling, that some of those bankers present at the meeting were later that very same day forced to deny that the group had not actually reversed their position and started selling.

And it was sell at any price. The story went that White Sewing Machine Company stock, having fallen from 50 to 10, could not find any buyers after lunch on the day of the crash, at which point someone, said to be one of the exchange runners, put in an order to buy a heap of shares at just one dollar. In the absence of any other bids he got all the stock he wanted. Claud Cockburn, a visiting English journalist, who just happened to have been invited to lunch at the home of a prominent Wall Street banker on the day of the crash, Sir Edgar Speyer, told of a sudden disturbance in the kitchen as the butler and footman served the main course of lamb. Four or five maidservants, of various ages had been standing behind the door rather agitated and angry. The butler begged Sir Edgar to come into the kitchen a moment and sort things out. The staff, it was explained to the visiting Cockburn, had their own ticker-tape in the kitchen and were all heavily engaged in the market…(Brooks, Once in Golconda, page 118.)

The glamour stock of the era was Radio Corporation of America, RCA. From $1.50 a share in 1921, the stock went to $574 in 1929; such was the speculative frenzy for the potential inherent in the new radio technology. Neither profits nor dividends had supported the fabulous rise. Those who tuned in late and bought in 1929 would not break even on such an investment until the mid 1960's.

In the end, the number of suicides told the story of woe. Legend says of course that the popular exit chosen was to jump from the window of the nearest tall building, however most, like the speculator J. J. Riordon, simply took a gun and shot themselves, Riordon having to go first to his bank (November 8) to get his pistol. The comedian Eddie Cantor gave strength to the suicide legends as part of his repertoire of jokes; had he not seen two speculators jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge holding hands because they shared a joint account ? Had he not overheard a hotel receptionist questioning guests checking in whether they came to sleep or to jump ?

The scams.

After the downturn had well and truly begun, the usual scams came to light, only this time on a hitherto unimaginable scale. What goes up…

The Vans; brothers Oris and Mantis Van Sweringen.

The Van brothers were born two years apart, but did everything together; one was never seen without the other. They lived in a huge Cleveland mansion but employed no servants, lived in just a few rooms, and slept in twin beds. (buyandhold.com, wall street history section.) The brothers had successfully developed several properties, resulting in good profits. In one of these property developments, they connected Shaker Heights to downtown Cleveland by rail. To do this, the Vans had made use of a holding company, a new development for the era, named the Nickel Plate Securities Coy, which sold stock to the public to raise the finance. The Vans must have liked it, for they embarked upon the process full time of buying and selling rail companies, floating stock and selling bonds to help it all along. A very complicated web of companies resulted, which the crash exposed in reality as one huge pyramid scheme, the holding company (the Allegheny Corporation) being used to manipulate earnings. (Not too dissimilar to subsequent events at Enron.) The whole put together was sponsored by the bank of JP Morgan. Again not too dissimilar to Enron – sponsorship by the banks.

Albert Wiggin.

"I think it is highly desirable that the officers of the bank should be interested in the stock of the bank."

Albert Wiggin was chairman of Chase National Bank. At the Pecora Commission of 1933, set up to look at the circumstances of the 1929 crash, it was revealed that chairman Wiggin had set up his own private corporation to bet on the shares of the bank of which he was chairman. Though not illegal in his day, beginning Sept 23, 1929, Wiggin went heavily short Chase Bank stock, (financed by a bank loan - which bank - his bank), which he bought back Dec 11 for a profit of some $4 million. Canadian registered companies were used to hide the gains. When the details subsequently became public, at one of the many inquiries held to explain the depression, Wiggin was forced eventually to settle with a group of disgruntled Chase shareholders for $2 million.

Sunshine Charlie - Charles Mitchell,

"Securities are manufactured, like so many pounds of coffee."

In 1921, Mitchell was CEO of National City Bank, a step up from his previous position, president of National City Coy, the securities arm of the bank. Banks did not have a charter to deal in shares, but got around this by owning subsidiaries to do it for them. Mitchell built a sales force to market shares and bonds to the rising middle class of the 1920's, eventually coming to underwrite over 150 bond issues, raising $10 billion. By 1928, Mitchell was the newly elected director of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, a position of some influence and prestige, whilst still flogging his bonds, many now of dubious quality. One raising, for the Brazilian state of Minas Gervais went ahead successfully despite the bank's internal report denigrating the ability of the state to pay any interest, let alone the principal. Ever the bull, Mitchell borrowed several million from his bank the day of the crash in an attempt to support the share price, which did not work. He was forced to resign his position in 1933, fronted court on tax evasion charges, later acquitted, despite admitting he hadn't paid taxes in years. The bank's stock price eventually hit bottom at just 4 percent of its 1929 peak.

The Swedish 'match-king', Ivar Krueger:

The Kreuger Group, (Kreuger and Toll) grew during the 1920's through a whole string of acquisitions by its owner Ivar Kreugar. By 1929 the Group controlled three-quarters of the worlds match production, built largely on debt to finance the buy out of competitors. Kreuger and Toll attracted a large following of small United States investors with the payment of regular and quite large dividend payments. As was discovered later however, much of the money to pay the dividends had been borrowed from various banks. The story goes that Kreuger himself would prepare the accounting statements, then have his accountants prepare the books to agree with what he had calculated the profit ought to be. Not surprisingly, the structure eventually collapsed in early March 1932 under the weight of debts and Krueger's own fraudulent activities. The collapse shook Wall Street to its foundations, and the ensuing scandal led to the passage of laws mandating the audit of the books of all companies listed on the exchange. Kreuger and Toll was one of the most widely held stocks and the largest bankruptcy of the time, until that is, the Insull Empire fell. Upon discovery of the fraud, the match king committed suicide in a Paris hotel March 12th, though there were rumors that it was murder.

DOW 1926 180's Chart

Samuel Insull:

"Bankers will lend you umbrellas only when it doesn't look like rain."

The empire Insull built fell, owing some $700 million - the largest corporate failure to that time. Insull worked originally under Thomas Edison, helping to build and run the first electric power plant in New York in 1881. Moving west, to Chicago, he built Middle West Utilities into a company that came to supply 12 percent of US power by 1912. It was one of Insull's companies that had helped make the 1893 World's Fair so brilliantly lit at night with the new wonder of electricity. Soon, Insull was acquiring or merging the interests of his and other electric concerns into the one listed vehicle, proving adept at handling the ongoing issuance of stocks and bonds with which to pay for it all. It was Insull that introduced the turbine to electricity generation, thereby vastly expanding the transmission powers of this new power source. The turbines drove ships, why not electricity, questioned Insull, by now christened the Aladdin of power. And it was he too, that suggested power plants should operate around the clock so as to offset the high costs of operation; that US homes should go all-electric; that US firms gear up for 'massing production', later shortened to mass-production. (Menschell, Markets Mobs and Mayhem, page 7.) It was worth a million dollars, or so it was said, to any man seen chatting with Sam Insull in front of his bank. (Holbrook, The Age of the Moguls, page 236.)

By the 1920's, US power supply was in the hands of just three entities, of which Insull owned one. The buying of legislatures to get favorable laws, and generous political contributions to those in power, was common. Constant expansion required ever increasing amounts of debt. Elaborate networks of cross-company share holdings were in place to fend off the constant threat of takeover. In 1928, investment bankers advised the formation of a new company, an investment trust, to own large blocks of shares in all the companies Insull operated. The IPO of the new company, Insull Utility Investments, offered at $12, hit the board at $30. Soon it was at $150. The investment trust became the owner of numerous cross share-holdings in all the Insull utilities, each highly leveraged so that any small rise in earnings had a disproportionately larger effect on holding company profits. Insull was not averse to see subsidiaries sell assets to each other at 'manufactured' prices either.

Insull's mighty corporation at first weathered the depression in reasonable shape, Insull had even managed well enough to have his company loan the city of Chicago fifty million dollars so that it might meet its payroll for teachers and police. (Menschell, Markets Mobs and Mayhem, page 7.) However continued low cash flow as the depression wore on brought down the interconnected network in 1934; the debt could no longer be serviced. Insull, charged with mail fraud and embezzlement, fled to Greece (not Canada), a country with which the US had no extradition treaty. He did however return to face the charges and was exonerated on all counts – the courts ruling that a holding company could not be held accountable for the acts of subsidiaries. But the fleeing had not won him public acceptance and destroyed his reputation. Insull died of a heart attack, penniless, in a Paris metro station (underneath the room of Krueger perhaps ?) though it was reported that he had beforehand reimbursed some of the investment losses of his employees, of which there were plenty, out of his own pocket. His investors though would get nothing and were mighty unhappy at the prospect if one is to judge by the 36 personal body guards that were employed to protect the Insull family day and night from the threats of shareholders no longer getting any returns from their Insull shares.

Richard Whitney:

Acting president of the NYSE in 1929, after then president E.H.H.Simmons decided upon an extended honeymoon in Hawaii, Whitney was officially elected president in 1930. It was discovered later however, that Whitney was living a lifestyle he could not afford, borrowing heavily, and then stealing, to cover up heavy 1929 stock losses. His thieving climaxed in 1937 with the embezzlement of $1 million from the NYSE itself, which was not much appreciated since the theft was from the Exchange Gratuity fund, set up to pay the estate of exchange members $20,000 upon death, of which Whitney was a trustee. Whitney went to jail for his crime, the only character of this era to do so.

There were plenty of other scams; including the wild money raising schemes of Charles Ponzi, the massive Florida land boom (close to Cuba, where a drop or three of legal whisky could be had cheaply in an otherwise purportedly dry America) a boom that was brought to a thumping halt by a Sept 18th 1926 hurricane, (already described) and the continuing saga of Oscar Hartzell and his 'Drake fortune swindle', but we have covered enough ground here for the moment.

Further reading:

Baruch, Bernard M. My Own Story, Henry Holt and Company, 1957.

Brooks, John. Once in Golconda, Harper & Row, 1969.

buyandhold.com, Wall Street History section (plenty of very good reading)

Chancellor, Edward. Devil Take the Hindmost, Papermac edition, 2000. (Chapter 7 in particular.)

Fridson, Martin S. It Was a Very Good Year, John Wiley and Sons Inc., 1998.

Gordon, John Steele. The Great Game, chapters 10, 11 and 12 in particular.

Green, Edwin. Banking; An Illustrated History, Rizzoli International Publications Inc.

Harrison, Fred. The Power in the Land, Universe Books, 1983.

Hoyt, Homer. According to Hoyt, 53 years of Homer Hoyt, 1916 to 1969, (collected works, no publisher listed)

Latham, Frank B. The Panic of 1893; A time of Strikes, Riots, Hobo Camps, Coxey's Army, Starvation, Withering Droughts and Fears of Revolution, Franklin Watts, Inc., 1971

Menschell, Robert. Markets Mobs and Mayhem. A Modern Look at the Madness of Crowds, John Wiley and Sons Inc., 2002.

Noyes A.D., Forty Years of American Finance, G. P. Putnam and Sons, 1909.

Porter, Glenn. The Rise of Big Business (American History series), Harlan Davidson Inc, 1973.

Simpson, Herbert D. Real Estate Speculation and the Depression, American Economic Review, XXIII no 1, March 1933

Sobel, Robert. The Great Bull Market: Wall Street in the 1920's, W W Norton & Co Inc, 1968.

Sobel, Robert. Panic on Wall Street: A History of America's Financial Disasters, Collier Books Edition 1972, (chapter 9 in particular).

Sprague, O. M. W. History of Crises Under the National Banking System, Washington, Government Printing Office, 1910.

Tuchman, Barbara. The Proud Tower, A Portrait of the World before the War: 1890 - 1914, Bantam Matrix edition, 1972.

Wicker, Elmus. Banking Panics of the Gilded Age, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Reader's caution.

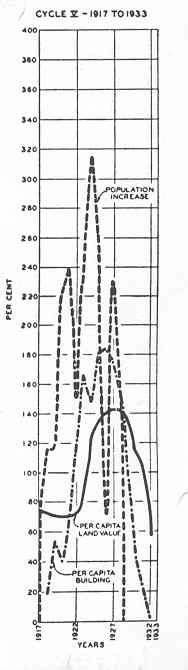

This cycle, (if we accept Hoyt's Chicago work as a guide), land price peaked before the stock market. This ought to give us caution as forecasters. Hoyt noted, page 265:

"notwithstanding these efforts to prop up real estate values from 1927 to 1929, the speculative public was forsaking real estate for the stock market. Land purchases no longer yielded quick cash profits, and real estate ceased to lure the crowds of new buyers who were being attracted by the fortunes that were being made in securities."