"My agency in promoting the passage of the National Bank Act was the greatest financial mistake of my life. It has built up a monopoly which affects every interest in the country. It should be repealed, but before that can be accomplished, the people will be arrayed on one side and the banks on the other, in a contest such as we have never before seen in this country."

Salmon P. Chase, Secretary of State and Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, quoted in Famous Quotations on Money, by Sheldon Emry.

It could well be imagined that by the civil war, the profusion of bank and other notes circulating within the US might have been more than a little chaotic. The civil war added yet another dimension to the problem when to pay for it, the North began the issuance of 'greenbacks', so called because of the color of the ink on the back side of the note. Significantly, these greenbacks were printed and issued by the government, not the banks, about which President Lincoln had a lot more to say. This made the currency known as fiat, or paper money, backed only by government say so and enforcement. The duel problems of the free-banking era and how to pay for the civil war led directly to the creation of a new banking system, completed with the passage of the National Banking Act of 1864.

This act of 1864 was attempting to do the following:

- provide a uniform note issue to the whole country that was also responsive to the seasonal demands of business, as when the farmers of the west required currency to pay for the harvest for example,

- reduce, if not eliminate the excess of notes, done effectively with the 10% tax on state notes, and

- most significantly, create a market for government debt.

As the civil war dragged unexpectantly on, more and more money was required, naturally, to pay for it. And just as naturally, the government again went into the debt of the bankers to do so.

Under this new national banking system, theoretically at least, anyone could still organize and open a bank, which now had to include the word 'National' within its name, and then apply for a charter from the newly created federal agency, the Comptroller of the Currency. Once this was done, the national bank then had to deposit with the Treasury, government bonds to the amount of one third of its capital. Hence the creation of a demand for government (Union) issued securities. The national banks could then issue notes up to 90% of either the par or market value of these securities, whichever was the lower. And all national banks had to accept the notes of other national banks at par.

So, after 1863, national banks bought government securities (bonds) deposited them immediately with the (federally controlled) Comptroller of the Currency and received (national) bank notes in return. The notes went into circulation as they were lent to those granted loans. "National bank notes were produced and distributed through an involved process. Once the basic engraving and printing was done (at first by private printers, later by the US Bureau of Engraving and Printing), the notes were entered on the books of the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, then returned to the printer where the seal of the Treasury Department was stamped on each. Next, the notes were shipped to the bank whose name appeared on them, where they were signed by two senior bank officers. The notes were then ready for circulation. National bank notes were the mainstay of the nation's money supply until the Federal Reserve note appeared in 1914." (factmonster.com) The design complexity of the notes was deliberate and intended to foil counterfeiters.

This gave rise to one situation, during and immediately after the civil war, when, because of the war effort, coin disappeared as a circulating medium. To counter this, 'paper coins' were put into circulation to replace the metal coin and help with the small payments and loose change.

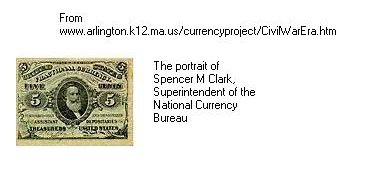

So paper notes of 3, 5, 10, 15, 25 and 50-cent denominations were printed and circulated. The Superintendent of the National Currency Bureau, Spencer Clark, in search of a design for the 5-cent note, decided to use his own. Congress, upset, promptly banned portraits of any living person on US notes from that time on.

The national banks, interestingly, were initially not permitted to accept real estate as collateral for loans, nor were they permitted to lend in excess of 10% of their capital base to any one borrower. The Comptroller of the Currency also required financial reports from each national bank, which was subject to possible audit as well. As the chapters show though, this still did not stop future bank crises.

Neither did the new pyramidal structure. "At the bottom of the pyramid were the numerous national country banks. These were national banks located anywhere in the country outside certain designated cities. Country banks were required by law to hold reserves equal to 15% of outstanding bank notes. Up to 60% of these reserves could be held as deposits in reserve city banks. All remaining reserves were required to be held as cash. The next level of the pyramid consisted of the reserve city banks. Reserve cities were specified by an act of Congress and consisted of large cities such as Boston, Philadelphia, and Kansas City. Reserve city banks were required to have reserves equal to 25% of outstanding bank notes. Half of these reserves could be held as deposits at banks in central reserve cities and half were required to be held as cash. Thus reserve city banks held deposits from country banks and could place deposits with central reserve city banks." (Mark Carlson, Causes of Bank Suspensions in the Panic of 1893, page 6.) Carlson noted further that: "In practice reserve city banks acted as pass-through banks, most of the interbank deposits they received from country banks were placed as deposits at central reserve city banks. New York City, and later Chicago and St. Louis, were designated as central reserve cities. Throughout the National Banking Era, New York was the primary central reserve city, holding a vast majority of the central reserve cities' interbank deposits." The chapters describing the cycles after 1860 give further details of some of the effects this caused.

The number of national banks expanded rapidly after 1863 and the number of state banks declined, as might be expected. State banks were not eliminated however and the ones that remained coexisted with the national system, albeit without the ability any longer to print their own notes. Another method of credit creation was soon found however, through the use of demand deposits; the loan granted to the customer would be credited to an account so created for the purpose, rather than issuing the formerly printed notes directly. Now, credit could be created merely with the stroke of a pen, rather than with the use of the old set of note plates and printing press. State banks were back in business. The number of state banks rose rapidly after 1885.

The increasing abundance of banks helped the industry in becoming a much more obvious and visible feature of the developing US economy. Edwin Green (Banking: An Illustrated History) pointed out: "By 1900 the head offices and branches of banks were landmarks of city centres…market towns, staging posts and smaller settlements. The appearance of these buildings was often grand and elaborate, as the architecture of banks was one of the few ways in which banks were prepared to advertise themselves. At corner sites of main streets these edifices could rival town halls and other public buildings in terms of their prominence and prestige, and some of the larger banks were already employing architects who specialized in bank design…At the outset of the 20th century these buildings reflected bankers eagerness to give a public impression of solidarity and permanence." (Page 87.)

As well the bankers did try for the impression of 'solidarity and permanence', because the way we have allowed banks to develop, their fractional reserve banking process creating credit on government granted licenses and privileges is exactly the opposite.

Follow up references:

Carlson, Mark. Causes of Bank Suspensions in the Panic of 1893, paper provided by the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.) in its Finance and Economic Discussion Series, number 2002-11.

Grossman, Richard S. US Banking History, Civil War to World War II, EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples, eh.net/encyclopedia/contents/grossman.banking.history.us.civil.war.wwii.php